THE QUIET CRISIS

By: Rafael Hostettler

Think of the word “crisis”. What comes to your mind? Nowadays, there is no shortage of crises all around, of every size and shape. Maybe your mind will wander towards the renewed re-armament of countries, in the face of so many military conflicts around the globe? Maybe it will invoke the recent Boeing 787 Max 9 door ripping out mid-flight, and almost resulting in a little boy being sucked out into the skies? Or the climate crisis? Against such a backdrop of mayhem and despair, it is quite understandable that very few think of daily care provision as something in crisis. And yet, the care crisis is as menacing as it is quiet.

There are reasons for this, of course. One is the lack of first-hand experience. Rarely does someone wake up one day thinking “Today, I just might walk into an elderly care home”. Care facilities are visited by necessity, rarely by chance or out of general curiosity, and even then only if your loved one was lucky enough to have obtained a place. The reality of what it means to be a carer for an elderly person is not immediately apparent to the vast majority of people.

To make matters worse, it is very difficult for caregivers, whether family members or professionals, to create public visibility for their problems. The barriers are many. For care professionals, the largest barrier is a big ethical conundrum: time taken to protest, for example to go on strike, is time of increased risk for those in their care. Becoming a caregiver is a calling – it is never the pursuit of social recognition or the lavish pay (both of which are lacking in this profession). Every professional caregiver I have met has a deeply rooted inclination to help others, making the idea of going on a strike – that is, to temporarily and purposefully stop delivering that help in order to raise public awareness – even less bearable than it might be for someone less empathetic.

For family members – usually women, who are very often sandwiched between having to care for small children and elderly family members all the while pursuing their careers – it is even worse. Who do you even go on strike against? Whole society? All while your elderly parents are declining at home and requiring more and more care as they are waiting for a state-subsidized place at a care facility, but the years pass by and no place is becoming available? The burden placed on carers is not only in terms of labour, but also emotional: there is a continued and pervasive stigma around complaining in public about being a carer for an elderly family member.

It is therefore quite unlikely that one might fully grasps the scope and scale of the care crisis. Rather, it is one of those wicked problems that you do not have any inkling of, or even remotely imagine exists, as long as you are not affected – and when it does affect you, it is too late to do something about it, because it is now dominating your life.

Put differently, if train drivers or farmers go on strike, the nation is annoyed: traffic is disrupted and the fresh produce we take for granted suddenly disappears. But if caregivers strike, people die – so how could they?

Every train not running or plane not flying immediately affects hundreds of people, hundreds of energetic and easily annoyed people that can start a protest on social media with the full force of their network. In contrast, a home caregiver might see thirty people in a day, none of them energetic and none of them will go and protest on social networks if the caregiver does not show up.

So whereas your average stranded passenger suddenly has a lot of time at hand to make some noise and protest, nobody in a care situation has the time, nor the will to risk the welfare of their patients. The quiet and invisibility of the care crisis is as deceptive as it is profound.

Given how extremely the cards are stacked against anyone trying to make noise for the care crisis, the fact that you nonetheless see it all over the news, should be frightening you to the core. To make it more tangible, let us look at the cold, hard truths of the numbers which underpin this crisis.

The Numbers and what they mean

Let us start with a very high number: 97.28%.

That is the percentage of the money people are entitled to spend for a daycare or nightcare spot in Germany, but cannot. Read that again please: cannot. Despite having paid into their care insurance their whole lives and despite being entitled to a spot, these places simply don’t exist. There is a less than 3% chance that you find one. That is like a classroom with only 1 table. Chances are good you are not the one getting it.

In Euros, those 97.28% of unspent financial entitlements amount to 40’000’000’000. 40 billion Euro that is, or the value of all the work rendered by Estonia (i.e. its GDP).

The amount of Pflegegeld (care money – you just need to claim it) and Pflegesachleistung (care service allowance – you need to spend it via professional services) that cannot be claimed due to lack of service are worth another 22.5 billion Euro, or three BER Airports.

In total, the gap between service entitlements and services actually paid out by the social care insurance is 74.4 billion Euro. That is about 577 Boeing 737 Max 9 airplanes – before discounts due to recent unscheduled door openings. Or about 1.5 times the national spend on the German army.

How is it trending? Well, up and with no limits: Social care insurance spending has surged from 38.5 to 60 billion Euro in just 5 years (2017 – 2022). That is a whopping 55% increase, and that all before the inflation of the last 12 months. But it is still less than the entitlements that could not be paid out.

Yes, you read that right, the sum of entitlements that ARE NOT paid out is larger than what IS paid out.

This lack of home care comes at massive costs: In a recent report, Barmer estimates that every year 1.3 million hospital visits could be prevented if more and better home care services were available. Very often the reason for admission is simply that they forgot to drink enough water and got dehydrated.

Let us round up with another very high number:

89% of ambulatory care services in Germany already had to reject customers.

Talking to care services, we have repeatedly heard that they increasingly need to “optimize” their customer base to survive. That means they can only take those customers that live at a location that fits geographically into a daily tour plan of their caregivers, and whose ailments work well from the funding and training perspective of their caregivers.

And if you were thinking that while this situation does indeed sound dire, it might be solved by the time you need care for someone you love, let me dispel that idea with this quote:

“The supply of care is being massively reduced despite rising demand, while insolvencies are increasing at the same time.”,

Wilfried Wesemann, Head of Deutscher Evangelischer Verband für Altenarbeit und Pflege e.V.

WHERE TO GO FROM HERE?

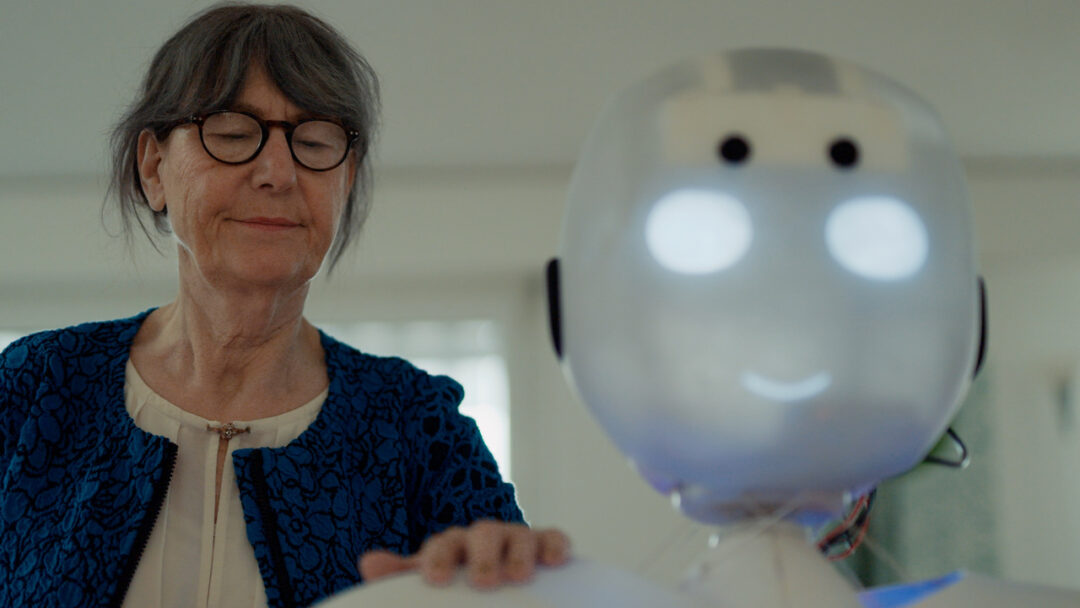

I hope it is clear by now why you are hearing about the care crisis, even though those suffering do so mostly silently. I think it is equally clear this crisis need to be acted on fast. At Devanthro, our purpose is to help people age with dignity in the comfort of their home and in caring company. We do this by super-powering caregivers, both professionals and relatives, to care for elderlies 24/7 from a distance with humanoid robotic avatars.

I know that our approach will have a significant impact – but we could move so much faster with your support! And really, it is in your own best interest.

Devanthro is a Munich-based robotics and AI business, building Robodies – robotic avatars for the elderly care market. Their partners include Charité Berlin, University of Oxford, and Diakonie. An early prototype is part of the permanent exhibition at Deutsches Museum in Munich. For more information, please visit https://devanthro.com/.